Archives

Blog

The Unspoken Reality of ADHD and Sleep

It’s 3:17 AM. I look over at the clock, and I could not be

Read More →

Blog

Reflections on Being a Father With ADHD

It’s a common feeling: you’ve read the parenting

Read More →

Blog

What Is (and Isn’t) an Executive Function Coach?

If you’ve heard the term executive function coach but

Read More →

Blog

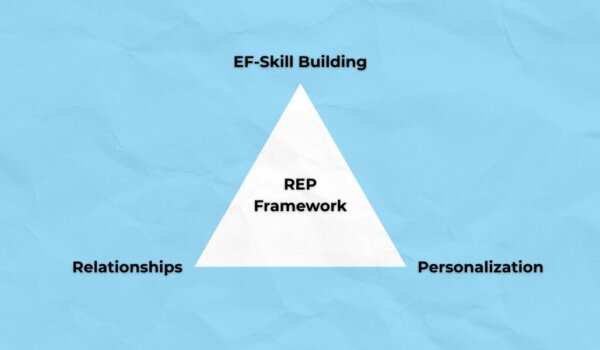

How We Coach Executive Function Differently: The REP Framework in Action

When a bright, motivated student continues to struggle in

Read More →

Video

A Research-Based Approach to Executive Function Skills

Executive function skills are the foundation for academic

Watch Video →

Video

Learning with AI: A Cognitive Science-Based Approach to Smarter Studying

AI shouldn’t replace your learning — it should upgrade it.

Watch Video →

Video

How a Skateboard Therapist Helps Teens Manage Stress & Anxiety

We know the end of the school year is intense for you and your

Watch Video →

Video

How an ADHD Coach Builds Executive Function in Students

ADHD isn’t about laziness or a lack of

Watch Video →

Video

The Truth About Impulsivity & Executive Function | Neuropsychologist Dr. Powell

Dr. Kristin Powell, Ph.D., ABPP-CN, is a board-certified

Watch Video →

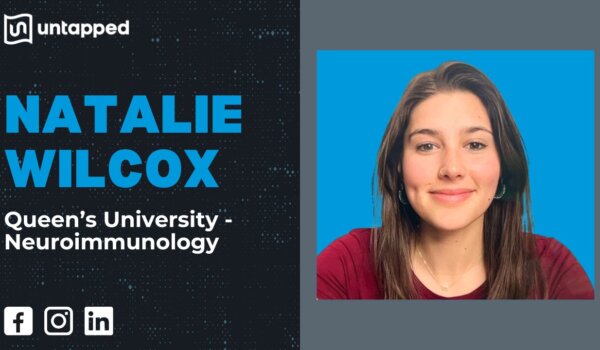

Video

The Simple Neuroscience of Studying

Natalie Wilcox, a master’s student specializing in

Watch Video →

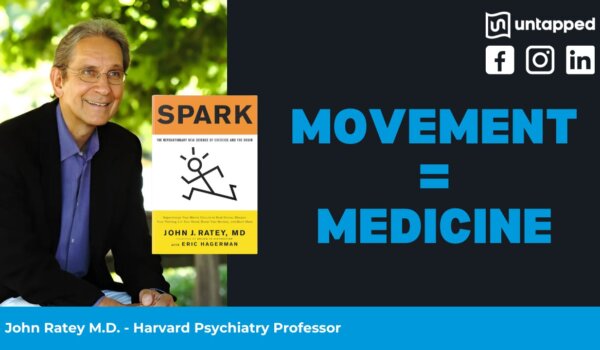

Video

Harvard’s Dr. Ratey: Why Exercise is Medicine for the Brain

What if the key to unlocking focus, motivation, and

Watch Video →

Podcast

Dr. Peg Dawson on Executive Function Development, Parenting, and Building Confidence in Your Child

Are you struggling to help your students develop the confidence

Listen to Podcast →